How Hudson Labs predicted Credit Suisse’s current day troubles without insider information

Credit Suisse is back in the news (did it ever leave?) with the conclusion of FINMA’s investigation into the bank’s spying scandal as well as the DOJ announcement about the settlement for the fraudulent loan for tuna fishing in Mozambique. Credit Suisse was flagged by our algorithms in early 2020, ahead of the Archegos and Greensill disasters.

When it comes to corporate crisis, two things are abundantly clear;

- Past transgressions predict future transgressions (think Wells Fargo) and

- Bad things correlate with each other. For instance, companies that rip off customers are more likely to commit securities fraud and companies that commit securities fraud are more likely to rip off customers (think Wells Fargo, Valeant Pharmaceuticals, Theranos etc).

In early 2020, Hudson Labs' algorithms identified Credit Suisse (CS) as high risk, a rating only ascribed to about 7% of large cap companies. High risk companies have about a one in three chance of receiving an SEC enforcement action. In Credit Suisse’s case, the company suffered significant financial losses due to appalling risk management.

Credit Suisse vs. its peers - A Deep Dive

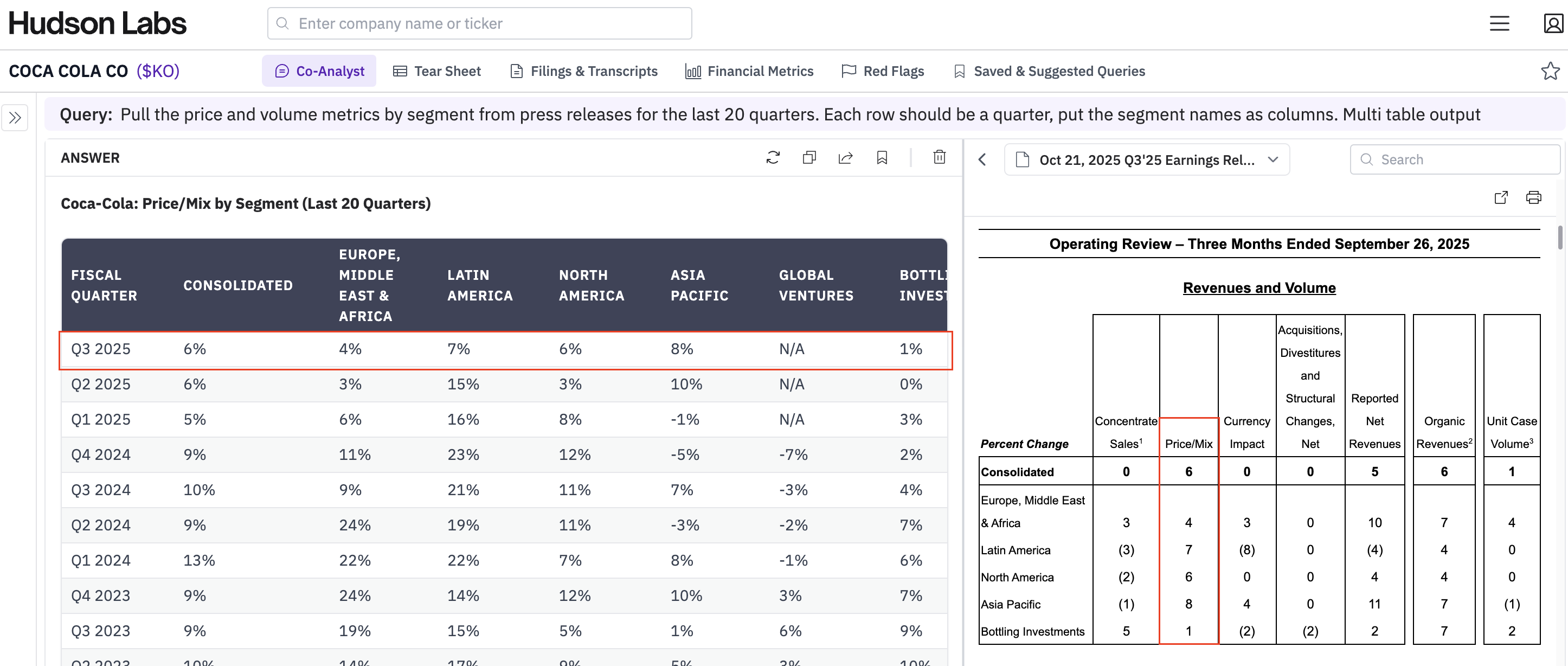

What made Credit Suisse more risky than their peers? We compared our algorithmic results for Credit Suisse (CS) to JPMorgan, Morgan Stanley and CIT Group (Competitors) to find out. (If this is your first time reading, learn more about what we do and how at www.Hudson-Labs.com.)

Hudson Labs extracted more than three times as many red flags from Credit Suisse’s 2020 annual report as compared to its competitors. More concerning, Credit Suisse had 22 high-importance red flags while its competitors had three or fewer. None of the competitors received a high risk score from Hudson Labs at the time.

Major red flags at Credit Suisse, as identified by our algorithms in 2020 include:

Credit Suisse had recently been busted in a scandal which involved spying on executives leading to the following management changes around the time of filing:

- CEO Tidjane Thiam resigned and was replaced by Thomas Gottstein.

- COO Pierre-Olivier Bouée resigned and was replaced by James B. Walker

- The company announced that CFO Paul Wirth would step down in May 2020.

- Peter Goerke, former Chief Human Resources Officer, and Joachim Oechslin, former Chief Risk Officer, stepped down from the “executive board”.

- Multiple board member resignations.

Credit Suisse also disclosed that “Executive Board members assumed other roles within Credit Suisse after stepping down from the Executive Board”, indicating that the cultural issues may not have been weeded out.

Credit Suisse was involved in an extraordinary number of regulatory investigations, beyond the spying scandal.

These investigations and inquiries discussed in the 2020 annual report included*:

- Investigations into the fraudulent loan for tuna fishing in Mozambique (recently resolved)

- Inquiries into money laundering by Bulgarian clients

- FIFA bribery and corruption inquiries

- Hiring practice investigations in the Asia Pacific region, involving settlements with both the DOJ and the SEC.

- COMCO investigation into setting foreign exchange rates.

- Internal investigations into a relationship manager who had recently been sentenced to five years in prison for fraud, forgery and criminal mismanagement. This investigation was expanded in 2018 to include other employees and CS’ controls.

- Settlements relating to Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities and the related financial crisis.

* Note the links to the articles are, in most cases, published after the 2020 filing and show the subsequent resolution.

In addition to the more obvious red flags listed above, many of the revenue increases that Credit Suisse touted in the year were attributable to one-time gains. One of these gains was generated by selling a minority interest in a trading platform to an affiliate (a related party). For those of you who are less familiar with financial analysis, major transactions with affiliates and related parties should be regarded with skepticism because it’s easier to fudge transaction values.

The bank had $32 million in loans outstanding to Executive Board members, including a whopping $17M outstanding to Helman Sitohang, CEO Asia Pacific. Credit Suisse was also subject to a $200M operating lease with a related party which is somewhat unusual for a bank.

While several of Credit Suisse’s competitors were implicated in the foreign exchange spot trading scandal and/or the mortgage backed securities settlements, overall the severity and frequency of scandals at JPM, Morgan Stanley and CIT Group were significantly lower.

While none of the red flags present at 2020 specifically indicated that Credit Suisse would overextend itself with Archegos or get involved with Greensill, there was extensive evidence that Credit Suisse had poor risk management compared to its peers. None of us should have been surprised at the recent crises, given the bank’s past. One benefit to a quantamental approach is that algorithms are able to understand the interaction of risks in multidimensional space. Without the algorithmic reminder of the frequency and severity of Credit Suisse’s transgressions, we are forced to rely on our gut feeling based on the number of times we’ve seen their name come up in an unfavourable light in the financial news. We also need to rely on the financial news to adequately cover the related risks. While many of Credit Suisse’s red flags were obvious and newsworthy, many of the more subtle flags like the gains on related party transactions were not covered in the mainstream.

For someone who’s not actively tracking Credit Suisse, relative to their peers, and reading their securities filings, it becomes hard to judge relative risk based on gut feel. Hudson Labs helps analysts scale their fundamentals analysis by automating detailed analysis of securities filings.

We would be amiss if we failed to mention that Credit Suisse is not the only investment bank that has been flagged by our algorithms in the past years. Unsurprisingly, UBS and DeutscheBank have received high scores from our algorithms. Goldman Sachs, while not very high risk, isn’t giving us warm and fuzzy feelings either. It is highly unusual for our algorithms to identify so many companies within one sub-sector as high risk. There’s been quite a bit of discussion about the world’s big investment banks being instigators or accessories to economic crises. Is there a bigger problem here that needs to be addressed?